Author: Gene Hsu

Abstract

When people talk about the Chinese language it is often assumed to refer to Simplified Chinese (SC) rather than Traditional Chinese (TC). Another misconception is that the Chinese used in China today is ‘orthodox’ compared to the Chinese spoken elsewhere. The assumptions, misunderstandings and myths that surround Chinese, and its differences in Taiwan, Hong Kong, mainland China and other countries and regions, create difficulties for interpreters and translators, as well as for those studying the language.

Many language service providers (LSPs) in the West have no clear idea about the fundamental differences between TC and SC. While many know that Cantonese uses Traditional characters, they may not be aware that Mandarin speakers in Taiwan do as well. Some think that the difference between SC and TC lies only in written characters, but it goes far beyond that.

To demythologise the Chinese language, this article begins with a brief history of the Chinese language, then discusses fundamental differences between Traditional and Simplified Chinese characters, and finally proposes resolutions to some problems when interpreting and translating from and into Chinese.

1. A brief history

Chinese characters have long been regarded as the core of Chinese civilisation, with calligraphy considered the chief of the ‘three perfections’ [1]. In ancient China, students were required to keep a clear mind while writing and hold the calligraphy brush rigidly; only by doing so would they be able to write Chinese characters as righteous as themselves. As an olden Chinese saying has it, “The character is like the person who wrote it” (字如其人).

TC was used for thousands of years until the simplification of Chinese characters started in 1956 under the Chinese Communist Party. As SC became an official script in China, Traditional characters were abandoned and stopped being taught in schools. The spoken language was also changed as vocabulary was restructured, merged, removed or simplified. Terminology differs between TC and SC in all areas – from movies and drama to school subjects, places and people. Many words were no longer used as they were, or the meanings of words were changed. Though some simplified characters have less strokes, the original and genuine meaning of traditional characters was lost as they were simplified, merged, removed and changed, etc.

KUNG Tzu-chen [2], a Chinese poet, calligrapher and intellectual active in the 19th century whose works both foreshadowed and influenced the modernisation movements of the late Tsing [3] dynasty, stated that “欲亡其國,必先滅其史;欲滅其族,必先滅其文化” (Literal Translation: To eliminate a country, one must first eliminate its history; to eliminate an ethnicity, one must first eliminate its culture) in his work “Ancient History of the Sinking II (《古史鉤沉二》)”. I was enlightened by his words and understood that to eliminate history or culture, it starts with eliminating its language, including letters and characters. What is lost in the Simplified Chinese language lies not only in the original meaning of each single Traditional Chinese character, but also that it cut the connections with ancient Chinese people and the five-thousand-year history and culture.

2. Layers of Meanings

There have been huge misunderstandings in terms of Traditional Chinese or Simplified Chinese in the Western world. Even many Language Service Providers (LSPs) have no clear idea about the fundamental differences between Traditional Chinese or Simplified Chinese. For instance, many people know Cantonese use Traditional Chinese, but they may not be aware that people still use Traditional Chinese characters in Taiwan today too. Some people think the difference between them lies only in written characters. As a matter of fact, it is far beyond that.

2.1. The Main Differences between Traditional and Simplified Chinese

One main difference between Traditional and Simplified Chinese lies in writing. Regarding the writing in Mandarin, they can vary geographically. For instance, in terms of the strokes of Chinese characters, some believe that it is easier to memorise characters with less strokes, so they prefer to use Simplified characters. Nonetheless, not all the characters in Traditional and Simplified Chinese are different from each other. Some can be the same, for example, “I” (我), “he” (他) and “she” (她) are the same in both Traditional and Simplified Chinese, respectively. While many others can also be very discrepant. To illustrate, the character for “listen/ hear” is “聽” in Traditional Chinese and “听” in Simplified Chinese; the character for “the saint” is “聖” in Traditional Chinese and “圣” in Simplified Chinese.

Moreover, each component of a Chinese character has its unique meaning, and they, as one body, integrate into one Chinese character, and the character has an original meaning. This will be explained further in 2.2. and 2.3.

2.2. The Meanings of the Chinese characters

As mentioned above, each Chinese character has its own meaning, and each component of a character has an original meaning too. “Love” is frequently mentioned in this topic. The traditional character “愛 (love)” (Wade-Giles[4]/ Chinese Pinyin[5]: ai4) has a heart with it while the heart was removed in the simplified version of “love”, that is “爱”. Many people said love without heart is meaningless. I would hereby like to give two examples to make it clearer. The character “listen/ hear” (聽) in Traditional Chinese has four major components: ear, eye, mind, heart. It means one uses ears to listen, eyes to see unspoken words, gestures, mind to think about what he or she heard, and listens to someone by heart. In the simplified character “听”, it has only two components, mouth and half a kilogram. It is evident that the simplified character loses the original meaning of “listen/ hear”. Moreover, we can imagine that it bears an almost opposite meaning of its origin – to shout or argue with others, calculate tiny things and be cunning.

Another example is the Traditional Chinese character “聖” (English: the saint), which has three main components: a bigger ear in the upper left corner, a smaller mouth in the upper right corner, and a person bowing in the lower body of the character, to show his or her modesty. This character means that to be a saint, one shall listen more, speak less and be humble. When it comes to the simplified version of the saint, “圣”, which has two components: the upper body of the character is “又” means “again” or “and”, the lower body is “土”, meaning “earth” or “mud”. Some argue that it looks like a person working on the farmland. However, we still cannot see this simplified version is linked to the saint.

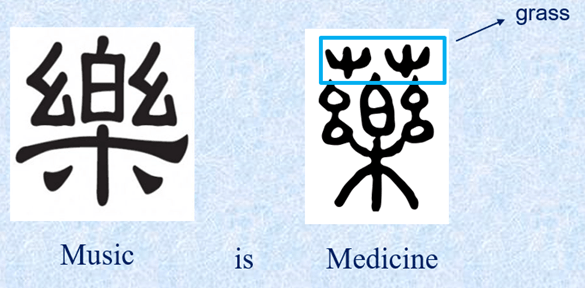

The Traditional Chinese character for medicine, “藥”, evolves from the Traditional Chinese character for music, “樂”, indicating that music and medicine are interlinked. Chinese culture believes that five tones correspond to the five elements, and the five elements correspond to the five internal organs. through the adjustment of music, can make the human heart reach a pure and peaceful state. In Traditional Chinese Medicine, the Chinese character for “medicine” is a combination of the characters for “music” and “grass”, suggesting music and herbs were traditionally considered essential components of medicine. Unfortunately, in SC, the character for “music” has evolved into “乐” which has almost nothing to do with its original meaning.

3. Vocabulary and Localisation

There are many differences between all kinds of vocabulary in Traditional and Simplified Chinese. For example, in terminology, the names of movies, dramas, school subjects, countries, places, and people.

Traditional Chinese or Simplified Chinese? It is a question. It is not only about the writing of characters, but localisation which requires words or terminology to be localised to make it more understandable for target audiences. There are two types of localisations, speaking and writing.

3.1. Speaking

When it comes to speaking in Mandarin, people may presume pronunciation is the same all the time. However, there are also differences in the ways TC and SC are spoken. To illustrate, the official pronunciation of the verb 包括 (‘incorporate, include, contain’) is ‘pao kuo4’[6] in mainland China (SC), but it is pronounced ‘pao kua’ [7] in daily conversations by some populations that use TC, including in Taiwan, Hong Kong and Chinese diaspora communities.

“Dating” is “拍拖” (Cantonese pinyin: paak3 to1) in Cantonese, while it is “yüeh hui4” (Wade-Giles) (Chinese pinyin: yüe1 hui4) (Traditional Chinese: 約會, Simplified Chinese: 约会) in Mandarin.

Besides, there is a subtle difference in articulation in spoken Chinese. For instance, erisation is often heard in the Northern China, while “er” is not commonly heard if a speaker is from the south of China or other countries and regions as the aforementioned.

3.2. Writing

Though not all the Traditional Chinese characters are different from the simplified versions, there are also differences between Traditional and Simplified Chinese characters. In the writing of Chinese characters, simplified characters were not merely simplified, but removed, merged, recreated, reformed or borrowed from Japanese kanji. Taking an example of List of Commonly Used Standard Chinese Characters (2013) [《通用規範漢字》(2013)], it is the current standard list of 8,105 Chinese characters. It has a list that also offers a table of correspondences between 2,546 Simplified Chinese characters and 2,574 Traditional Chinese characters, along with other selected variant forms.

In the writing of Chinese characters, simplified characters were not merely simplified, but removed, merged, recreated, reformed or borrowed from Japanese Kanji. For instance, the second character “fu4 / fù” of “答覆” (reply, answer), “恢復” (restore, recover), “重複” (repeat) are all different in Traditional Chinese, while in Simplified Chinese, they are all lost and “复” is used to replace all the three characters. The pronunciation of “silence” (沈默) and “sink” (沉没) is the same in Mandarin, and it spells as “chen2 mo4” in both Wade-Giles and Chinese pinyin. Nevertheless, in the way of writing, it is different. The first character of two words in Simplified Chinese is the same, “沉”. In Traditional Chinese, however, the first character of “silence” is “沈” while that of “sink” is “沉”, although you may see “沉” is used for “silence” on some occasions in Taiwan.

Furthermore, another major difference between Traditional Chinese and Simplified Chinese is in translating terminology including names of people, places, and educational subjects. For instance, Sydney is 雪梨 in Taiwan (TC) and 悉尼 in China (SC). New Zealand is 新西蘭 in China (新 meaning ‘new’) and 紐西蘭 in Taiwan and Hong Kong (as the pronunciation of 紐 and ‘new’ is almost the same). Thus, both Chinese versions are acceptable.

In addition, some were borrowed from Japanese kanji, as many Chinese scholars had been studying in Japan since the Meiji Restoration (1868). As a result, they introduced a lot of Japanese kanji into modern Chinese, please see the table below.

| Terminology borrowed from Japan | Economy | Society | Art |

| Traditional Chinese | 經濟 | 社會 | 藝術 |

| Japanese | 経済 | 社会 | 芸術 |

| Simplified Chinese | 经济 | 社会 | 艺术 |

4. Traditional or simplified?

Some people prefer SC characters because they find it is easier to memorise characters with fewer strokes. Preferences also vary geographically. In business, the choice is partially about localisation and this may differ depending on whether you are speaking or writing. When interpreting and translating from or into Chinese, the following elements should be considered: the target audience or reader, the hidden meaning of the source language, culture and history in both source and target languages, and the purpose and goal of the translation/interpreting.

There is one main rule translators can follow to determine which version is appropriate: ask the client which version they require and check in which region/country the translation will be used. In terms of language learning, culture and history, I would recommend starting with TC: once you understand the origins of the language, it should be easier to learn the simplified version.

Notes

[1] Pellatt, V, Chen, YY-Y and Liu, E (2014) Translating Chinese Culture: The process of Chinese-English translation, London and New York: Routledge, 29

[2] Kung, T-C (b.1792-d.1841) 古史鉤沉二 (Explorations in Ancient History, Part 2)

[3] I use the Wade-Giles system of romanising modern Chinese here. Originally developed by Thomas Wade in the mid-19th century to simplify Chinese-language characters for the Western world, the system was developed in Herbert Giles’s Chinese-English Dictionary (1892). Chinese pinyin was outlined in 漢語拼音方案 (Scheme for the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet) in the 1950s and 1960s, based on the Beijing dialect of Mandarin.

[4] Wade-Giles: Wade-Giles romanisation, system of romanising the modern Chinese written language, originally devised to simplify Chinese-language characters for the Western world. (https://www.britannica.com/topic/Wade-Giles-romanisation) It developed from a system produced by Thomas Wade in the mid-nineteenth century and reached settled form with Herbert Giles’ Chinese-English dictionary of 1892. (https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Wade-Giles)

[5] Chinese pinyin: The pinyin system was outlined in “漢語拼音方案” (Scheme for the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet) in between 1950s and 1960s. Pinyin romanisation, system of romanisation for the Chinese written language based on the pronunciation of the Beijing dialect of Mandarin Chinese. (https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pinyin-romanisation)

[6] Wade-Giles romanisation: Its Chinese Pinyin is bao1 kuo4. Though the spellings are different in Wade-Giles romanisation and Chinese pinyin systems, the pronunciation of “包括” is the same.

[7] Wade-Giles romanisation: Its Chinese Pinyin is bao1 gua1. Though the spellings are different in Wade-Giles romanisation and Chinese pinyin systems, the pronunciation of “包括” is the same.

Article publication

“Chinese: over-simplified?“, Winter Issue, Vol 64, No. 4, The Linguist (paper edition and electronic version), p. 33.

Archive: please click here to check the archived file of the condensed version of this piece published by The Linguist.

NOTE: “Chinese: over-simplified?” is a condensed excerpt from this piece. Owing to word-count limitations, they weren’t able to publish the full article.

About the author

Gene Hsu, a professional interpreter and translator as well as a singer-songwriter-ethnomusicologist. Gene is engaged in intercultural and interdisciplinary research in music and translation. She has presented her papers at academic and professional conferences around the world. Furthermore, her research draws attention to the historical and intercultural significance of traditional languages, song writing and song translation. Gene hopes to bridge cultural and language gaps and to contribute towards better understanding and world peace.

For more information about her research and work, please visit https://versevoice.org/research/ and https://veritastranslates.com/

Follow us on IG: versevoiceorg

Follow us on Facebook: Verse & Voice

Leave a comment